Housing explained

Supportive housing is permanent, affordable housing that’s paired with on-site services, like mental health care, job training, and addiction treatment.

It’s for especially vulnerable people, like those with disabilities or survivors of trauma, who otherwise have difficulty staying in stable housing. A study by Columbia University found that after moving into supportive housing, about 90% of residents were still stably housed after two years, compared to only 42% of people who were not given access to supportive housing. Simply put, affordable housing combined with specialized services is a proven method to end the most persistent and acute homelessness.

It’s important to know that supportive housing is safe and fits into the community. Most people who live near supportive housing don’t even realize it, because supportive housing structures look no different than other condo or apartment buildings. And because there are professional staff and security on site, supportive housing buildings actually can make the communities around them safer.

These apartments are not free to the residents, who have to pay 30% of whatever income they have. There is no time limit on how long residents can stay because they often have disabilities or complex challenges. The goal, however, is for all residents to be able to live stably, on their own.

One of the key features of supportive housing is that it’s community oriented. Homelessness is dehumanizing and isolating. Supportive housing typically features communal spaces, group activities, and even shared apartments to help people regain a sense of belonging and support.

Supportive housing is designed for people who need access to supportive services in order to achieve stability. These are people who may have experienced chronic homelessness, which means they’ve been without a home for more than a year, they’ve experienced homelessness at least four times in the last three years, or they have a complex set of disabilities. To put it another way: These are people who have a difficult time staying in stable housing, whether it’s because they’ve experienced severe trauma or have a disability.

According to the 2022 Homeless Count, two-fifths of the people experiencing homelessness in L.A. County need supportive housing. The rest attribute their instability to economic hardship and the low supply of housing they can afford. That’s where affordable housing comes in.

Affordable housing is essential, because most people experiencing homelessness simply can’t find a home they can afford.

Affordable housing units rent for less than the market rate and are reserved for people who earn less than average income. Some developers specialize in affordable housing, while others may make some units in their buildings affordable in order to access tax breaks or other incentives.

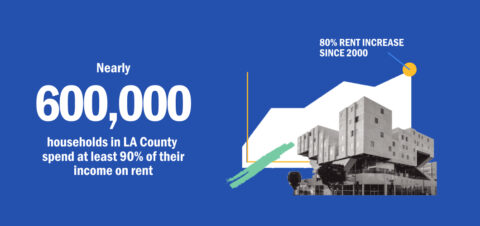

According to the Public Policy Institute of California, Los Angeles County has a poverty rate of 13.7%—the highest in the state. This partially due to the fact that county residents pay 80% more in rent today than they did in the year 2000, while average renter income has decreased by 4% over that same period of time. As a result, nearly 600,000 L.A. households spend at least 90% of their income on rent.

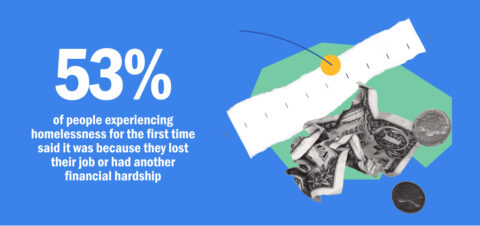

The result is the worst homelessness crisis in America. According to the 2019 Homeless Count, 53% of people experiencing homelessness for the first time said it was because they lost their job or had another financial hardship.

For thousands of people experiencing homelessness, the answer is affordable housing. These apartments aren’t available to just anyone who can afford them. They’re reserved for people who meet specific income criteria, typically 0-80% of the average income in the area—also known as “median income.” The scale slides based on how many people are in the household.

This can all get complicated pretty quickly, but here’s the point: Most people experiencing homelessness just need a place they can afford, and we don’t have enough of those options. Creating affordable housing is a guaranteed way to bring people off the streets while preventing the kind of trauma and economic struggles that could keep them there.